This is the second installment in a recap series that aims to summarize the reported cases coming out of the Maryland appellate courts: the Maryland Court of Appeals, and the Maryland Court of Special Appeals. Detailed by Joseph, Greenwald & Laake associate, this document provides a synopsis of the Courts’ opinions.

In our first installment, we covered cases decided by the courts since January 2022. Read on as we progress through more recent cases tackled in Maryland.

(Note: The Maryland Court of Appeals’ attorney grievance and bar matters will not be covered.)

Paula v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore

This case involves two Plaintiffs, both Baltimore City residents, who filed suit against the City of Baltimore over its alleged mismanagement of the Civilian Review Board (CRB). The CRB is a statutory agency that processes and investigates complaints about law enforcement officers from the public. The City filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, arguing that the Plaintiffs did not have the standing to bring the suit. The Circuit Court agreed and dismissed the suit. This case, in essence, is about standing, the doctrine that ensures that a party filing a lawsuit has a real interest in the outcome and that an actual controversy or dispute has occurred that the court can resolve. By reviewing this case, we can see how standing operates in the legal system.

On appeal, the Plaintiffs argued that the dismissal of their suit was erroneous as they had standing to sue the City. First, they claimed that the alleged mismanagement of the CRB uniquely aggrieved them in comparison with other Baltimore City residents. Additionally, they argued that they had a right to a properly functioning CRB as stated by its establishing statute. This issue, they claim, could be vindicated through legal action. This is called normal standing. Second, they argued that they had taxpayer standing. This version of standing allows a taxpayer to sue the City if an illegal or unauthorized action by the City causes the taxpayer unique monetary loss or an increase in the taxes they owe. Lastly, they argued that Articles 9, 19, and/or 24 of the Maryland Declaration of Rights gave them standing to sue the City.

The Maryland Court of Special Appeals rejected each of these arguments. First, the Court found that the Plaintiff’s interest was not personal. It was noted that the CRB exists not to redress specific instances of misconduct to the complainant but to maintain the integrity of the Baltimore City Police Department as a whole. Critically, the Court held that the Plaintiffs were never denied the right to file a complaint. Instead, the complaint was contested only after it was filed. Second, the Court held that the Plaintiff’s status as Baltimore City taxpayers did not give them standing because the alleged mismanagement of the CRB did not cause them specific monetary harm. Significantly, the Plaintiffs failed to connect the CRB’s alleged mismanagement to expenditures or inefficiencies that would have been avoided if the CRB was properly managed and sufficiently independent from the City’s control. Lastly, the Court held that the Plaintiffs did not have standing under Articles 9, 19, or 24 of the Maryland Declaration of Rights.

- Article 9 provides that only the General Assembly can “suspend Laws, or the execution of Laws.” The Plaintiffs never argued that the law establishing the CRB had been effectively suspended by the City. Instead, they only claimed that the City was violating the CRB statute. The violation of a law is not the same as its suspension.

- Article 19 provides access to the Courts. The Court held that the Plaintiffs were not denied access to the court system. The trial court held, and the Court of Special Appeals agreed, that there was simply no injury to the Plaintiffs specifically that the courts could redress.

- Articles 24 provides a right to due process of law. The Court found that the Plaintiffs were not deprived of any right without process. Only law enforcement officers who are subject to possible discipline from the CRB are entitled to due process protections under Article 24. This does not include those who file complaints with the CRB.

This case is best understood as an application of the principle that there is no right that can be vindicated in the judicial system which entitles a citizen to “good” governance unless the alleged “bad” governance affects them differently than it affects the rest of the public.

Playmark Inc. et al. v. Perret

This case involves James Perret, the Plaintiff, who was employed by AAA, Inc. In 2000, AAA agreed that if Perret continued to work for AAA in a managerial capacity from 2000 until 2015, AAA would pay Perrett $25,000 per year until 2025. By reviewing this case, the obligations of corporate successors will be illuminated.

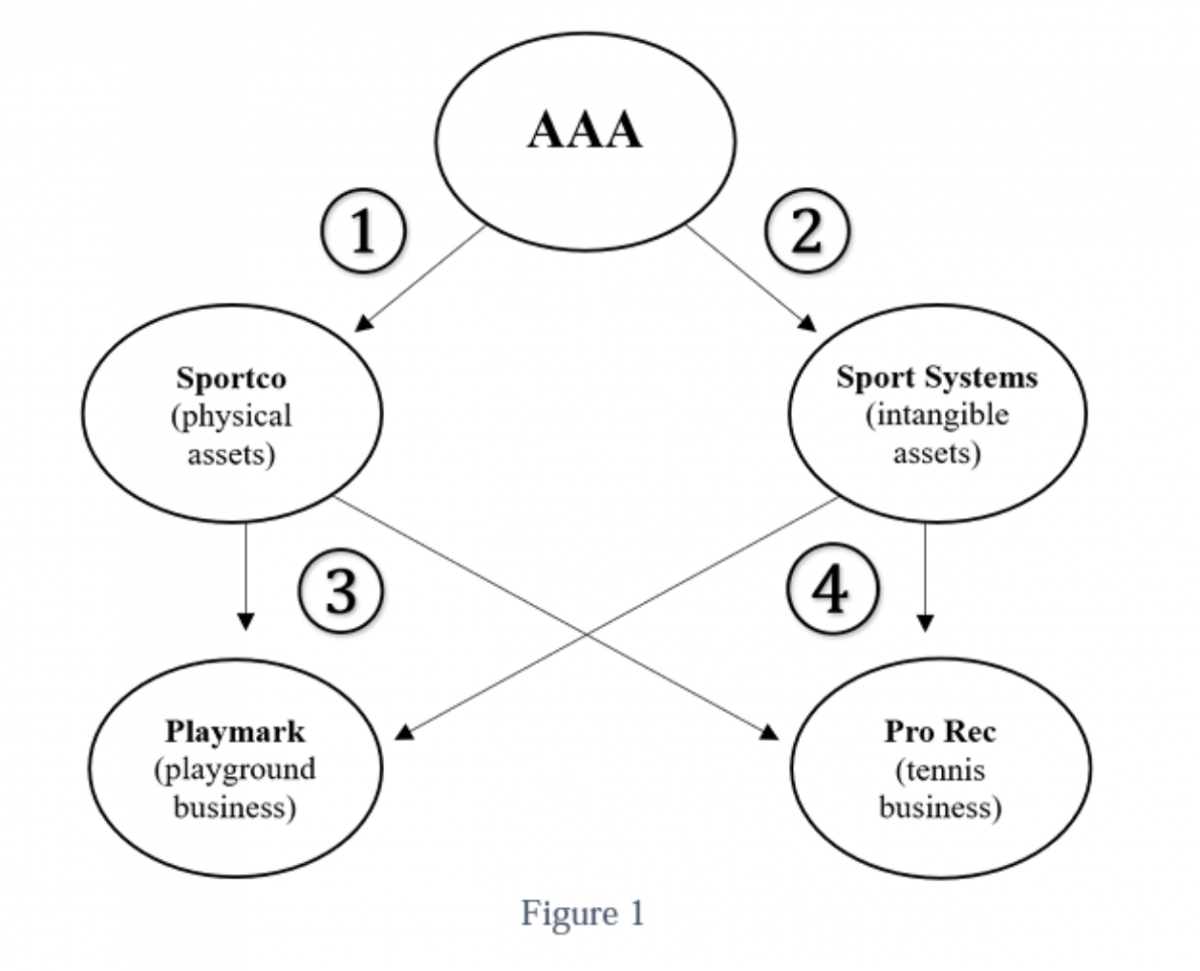

In 2005, AAA was split up into two separate entities that continued to provide the same services. After this company shift, Perrett was still employed in a managerial capacity. In 2015, Perret started to receive the $25,000 payments. The payments ceased, however, when the owners of the AAA successor entities, who were previously married, got a divorce. This effectively split the two successor entities again—into Playmark and Pro Rec—so they could each maintain half of what they previously owned prior to the divorce. They, then, parted ways.

James Perrett filed suit against Playmark and Pro Rec, alleging that by failing to make the $25,000 annual payments, they had breached the contract agreed upon in 2000. He also alleged, both additionally and in the alternative, that the failure to make the annual payments violated the Maryland Wage Act, which prohibits the wrongful withholding of wages by employers upon termination. The trial court agreed with Perret by finding that Playmark and Pro Rec did breach the 2000 agreement. It was found that the two companies were liable for the annual payments due to Perret. The trial court, however, rejected Perret’s arguments under the Maryland Wage Act. Playmark and Pro Rec appealed the ruling on the breach of contract claim, and Perret cross-appealed the ruling on the dismissal of his Wage Act claim.

The Court of Special Appeals affirmed the trial court’s ruling on the breach of contract claim and held that Playmark and Pro-Rec were obligated to make the annual payments to Perret. This is because, ultimately, they were the successors of the initial corporation, AAA. Meaning, that they had explicitly agreed to assume the obligation to pay Perret. The Court included an illustration in its opinion that shows how AAA became two separate entities, which were then divided again into two more entities.

The Court of Special Appeals reversed the trial court’s dismissal of Perret’s Maryland Wage Act Claim. The effect of this, though the Court noted, is likely negligible as the damages under the contract action and the Maryland Wage Act are the same. The only difference is that, under the Maryland Wage Act, a plaintiff is entitled to three times the damages sought, attorney’s fees, and costs if they can demonstrate that the employer’s failure to pay the money owed was “not as a result of a bona fide dispute.” The case was remanded to the trial court for further proceedings on Perret’s Maryland Wage Act claim.

This decision should stand as a reminder to businesses that unwanted corporate obligations do not disappear. Even a clever corporate restructuring designed to avoid successor liability by dividing assets in such a way that no successor acquires “substantially all” the assets of the former corporation, as was done here, will not avoid successor liability. Instead, if half of the assets of a company are transferred to two successor entities (or a third to three, or a fourth to four, etc.) each of the entities that together acquired the assets will be held liable for the obligations in proportion to the assets they acquired.

Beckwitt v. Maryland

This peculiar and tragic case involves Beckwitt, a paranoid millionaire fearing nuclear war. Beckwitt hired Askia Khafra, a young man whose company Beckwitt had invested in, to dig tunnels beneath his home in Montgomery County. The tunnels would become littered with trash and debris. Beckwitt provided power to the tunnels via a series of extension cords and power strips. Hours before a fire broke out in the tunnels, Khafra informed Beckwitt of a power failure. Khafra was killed in the fire.

A jury in Montgomery County convicted Beckwitt of involuntary manslaughter and depraved-heart murder. The Court of Special Appeals affirmed the involuntary manslaughter conviction and reversed the conviction for depraved-heart murder. While Beckwitt demonstrated a “wanton and reckless” disregard for Khafra’s life, his conduct did not rise to the level of “extreme disregard for human life reasonably likely to cause death” that was needed to sustain the depraved-heart murder conviction. The Court of Special Appeals explained that hiring someone to dig tunnels underneath their home does not rise to the level of opprobrious conduct that a conviction for depraved-heart murder requires.

Beckwitt appealed the Court of Special Appeals’ affirmation of his manslaughter conviction and raised several arguments, some of which are not addressed here because they were not essential to the result of the case on appeal. The State appealed the reversal of the depraved-heart murder conviction.

First, he argued that under pre-1776 English statutes, which prohibited prosecution against someone in whose home an accidental fire started, the state could not hold him criminally responsible for the fire. Therefore, the court lacked jurisdiction over the criminal prosecution. The Maryland Court of Appeals held that Beckwitt’s argument did not implicate the trial court’s jurisdiction, and therefore could not be raised on appeal. After a well-researched and informative explanation of why the pre-1776 statutes were inapplicable, the Court wrote that even if the old English statutes were applicable in Maryland, the fire that killed Khafra was not accidental. Instead, Beckwitt was convicted because the conditions he created in his basement and the tunnels made it so that Khafra could not report and escape from a potentially life-threatening situation.

Beckwitt also argued that he could not be convicted for involuntary manslaughter based on gross negligence. Hiring Khafra to work in his home with hoarding conditions and power outages was not likely to cause harm to the person. Hoarding, he argues, is not inherently dangerous conduct. His conduct, therefore, was not a “wanton and reckless disregard for human life” necessary to support the conviction for involuntary manslaughter. The Court of Appeals held that there was sufficient evidence for the jury to find that Beckwitt’s gross negligence caused Khafra’s death. The Court of Appeals held that “on multiple levels, Beckwitt’s conduct constituted a departure from the conduct that a reasonable person would have engaged in under similar circumstances. No reasonable person would have required Khafra to live and work in a basement with a faulty supply of electricity for light and airflow and without a reliable way for Khafra to contact him. No reasonable person would have maintained the abhorrent conditions that existed in the basement with debris and trash blocking Khafra’s route out in the event of an emergency. And no reasonable person would have reacted as casually as Beckwitt did on the day of the fire upon learning of the two power outages in the basement.” The Court also wrote that Beckwitt, as Khafra’s employer under Maryland law, had a legal duty to provide safe working conditions and a jury could have potentially convicted him of involuntary manslaughter on that basis also.

The Court of Appeals affirmed the Court of Special Appeals’ reversal of the depraved-heart murder conviction. While Beckwitt acted strangely, negligently, and recklessly, he did not act with the “extreme indifference” necessary for depraved-heart murder.

After the Court’s ruling was issued in January, Beckwitt was resentenced to five years in prison, much of which he has already served.